Imagine a Pacific Northwest city close to the US-Canada border that boasts lush forests, stunning nearby mountains, a small working harbor with a cruise ship terminal, and a population of around 90,000 people. If you hail from the US, you might say this sounds a lot like Bellingham, Washington, but if you’re on the Canadian side, you might identify it as the City of Victoria* in British Columbia.

Good news, you’d be correct either way.

While Victoria and Bellingham have much in common, they could never be confused with each other. For one, Victoria is situated on an island and is the provincial capital of BC. Bellingham, by contrast, is a mainland town and lies 149 miles/240 km north of its state’s capital, Olympia.

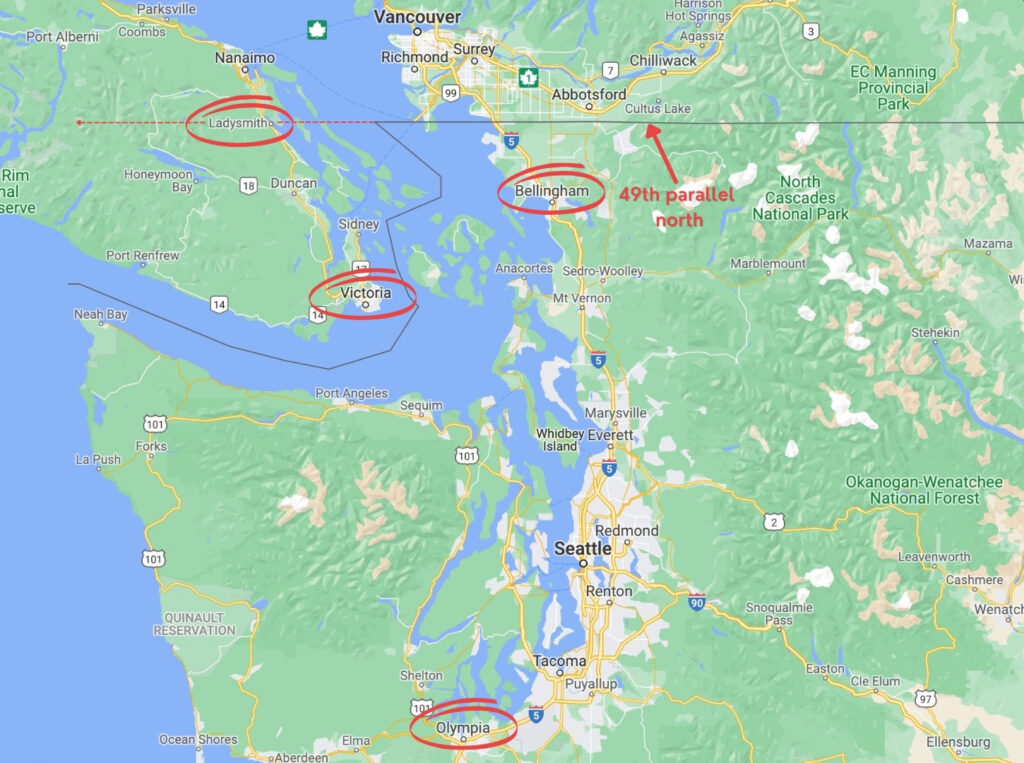

Fun Fact: Despite being a Canadian city, Victoria is actually located farther south than Bellingham because the US-Canada border deviates from the forty-ninth parallel line, detouring below the southern tip of Vancouver Island. Had the forty-ninth parallel continued its more-or-less straight trajectory west, it would have sliced right through the town of Ladysmith, 55 miles/89 km northwest of Victoria.

Coincidentally, I have a history with both cities, Victoria being my hometown, and Bellingham being home to an aunt and uncle who once owned a small hobby farm on the outskirts of town. I was a teenager when they sold that property and moved back to Canada, and regrettably, I never got to explore it as much as I’d wanted to. However, I will always remember being happy and comfortable there, perhaps because of the similarities to my own city.

I’ll get back to the point of this comparison in a moment, but for now, what’s important to say is that Victoria—not Bellingham—seemed like the perfect backdrop for my debut novel, TimeBlink. It was the natural choice. Beginning writers are often advised to “write what you know,” and I certainly knew Victoria and its surrounding area well. To boot, it’s a city known for its heritage architecture, its fantastic shopping and dining, and its abundant natural beauty. Why wouldn’t I feature it in my book? And thus, after a quick name change, Port Raven was born, a combination of my late parents’ names, Lorraine and Alvin.

Throughout the four-year process of writing TimeBlink, I adhered to this vision staunchly. It was important to me that the story took place in Canada, specifically paying homage to my hometown of Victoria. I would, in turn, use Canadian English (which is, not too helpfully, a mix of British and US English rules), and I would reference songs by The Tragically Hip and mention the Vancouver Canucks if appropriate. I stuck to my guns and completed my proudly Canadian-flavoured (see how I did that?) novel near the end of 2019.

Unfortunately, this coincided with my newfound addiction to writer groups on social media.

It was there I would spend hours soaking up the opinions, stories, and advice of other independently published authors. They were my heroes. Real-live people living the indie dream. I should therefore trust them inherently, right? It was through these groups (coupled with my other escalating habit of googling everything) that I discovered a somewhat common belief among writers from Canada and other predominantly English-speaking countries that it would be unwise—or even reckless—to base a story anywhere but the United States and to furthermore write it in anything but US English. That is, if one wished to sell books in the extremely lucrative US market, which holds a whopping 30% share in the global publishing market (2017).

Okay, sure, I said. But aren’t there plenty of hugely successful novels set in Canada, written by Canadian authors? What about Atwood, Munro, MacLeod, and Penny? Besides, American readers aren’t stupid. Surely they’d understand the differences and perhaps even embrace them. The answer was always the same: It wasn’t that a Canadian novel wouldn’t sell at all in America. It was that a book would have a better chance at success if it didn’t include the distractions of Canadian spellings, idioms, and culture.

It was a sound argument. As an unknown writer, was I screwing my shot at success right out of the gate with my stubborn allegiance to my country? Might I need to rethink my strategy?

Little by little I softened.

No, I wasn’t excited about erasing Canada from my book. The idea of it wasn’t only daunting at this late stage of the game, it was also downright annoying. I secretly resented my American counterparts who went about their days blissfully penning their novels without ever having to give this issue a moment’s thought. Did they know how lucky they were?

Once I finally understood the value of taking this step and set to work on the edits, my thoughts went immediately to my fellow Canadians. Would they reject my work? Accuse me of selling out? I concluded they probably wouldn’t. We Canadians are known as a generally kind and tolerant bunch.

But then a new emotion set in: doubt. How much did I really know about our neighbors to the south? Could I pull it off? Would my Canadian editor catch all the nuances? Would my American readers see right through it? Truthfully, I felt a little like the great and powerful Oz, working his magic deceit behind the scenes. Would someone pull the curtain back and expose me for the imposter I was?

Fortunately, my novel’s setting is more of a decoration than a plot-advancement tool, so I didn’t have to be too specific. In a more location-driven novel where the place is sometimes a character in itself (Harry Potter, The Hunger Games, and Where the Crawdads Sing), I wouldn’t have been able to make this eleventh-hour modification so easily. Furthermore, setting isn’t necessarily a physical place at all. It is also the time the story occurs including time of day or even time period in history (or future). In that way, my setting in the true sense of the word could be retained (a rainy west coast town); it was only the exact physical location that needed to be revisited.

Hooray for small victories. But the switch to an American town required research.

Changing the location to appeal to a wider audience meant I had to first go in and revise all the language. Favourite became favorite. Washroom became either restroom or bathroom, depending on where it was located. Travelling became traveling–and given it was a time-travel novel, I really had to get this one right. In the end, I found a great resource detailing why it should be spelled with one L instead of two.

Then I needed to research the crap out of Bellingham because it seemed like the next best place in which to let my characters do their character things. Sure, I’d spent time there in my youth, but beyond numerous trips to Fred Meyer’s and The Royal Fork Buffet with my family, I had no clue what made it tick. As I pored over my seventh realtor-sponsored article about the virtues of living in Bellingham, I had an epiphany: TimeBlink was fiction.

Well, duh.

Please don’t judge. I’m new at this. I’d been so busy trying to make the story believable that it never occurred to me that it need NOT be so literal! I could craft any world I wanted, name it whatever I wanted, and populate it with freaking Martians if I wanted! (I didn’t.).

That was the moment in my writing journey I understood the power beneath my fingertips.

What an exquisite gift to be able to craft something beautiful or terrifying or tender out of thin air. It is an even bigger gift when your reader feels a tangible connection to that world you’ve created expressly for them.

Armed with this sunny new outlook, I came up with a new plan: 1) leave the Americanized spelling edits and vernacular intact (since they are widely used and accepted anyway) and, 2) employ a purposely vague strategy when it came to describing the physical location. It wasn’t a choice of whether I should place Port Raven within the boundaries of Canada or the United States. It could be anywhere.

Chances are, you’ve heard of Castle Rock.

For those of you who haven’t, Castle Rock is a fictional Maine town that appears in several of Stephen King’s novels and serves as either the primary setting, such as in The Dead Zone and Needful Things, or mentioned in passing in others, like in 11/22/63. King is the master of world-crafting. His depictions are so clear that after reading his books, you would swear Castle Rock (or Derry or Chester’s Mill) might actually exist. Genius!

Never would I compare myself to a writer of Mr. King’s caliber, but I did borrow a page from his book. Using his fake-city blueprint and real places inspired by my hometown, I had the freedom to mix and match streets, restaurants, beaches, and parks at will. In one scene I mention “a group of small islands scattered up and down the coast” that could very well represent the San Juans or the Gulf Islands or any islands really, but in reality, they exist only in my mind.

Fun Fact: TimeBlink‘s Chapman Falls was inspired by Sitting Lady Falls at Witty’s Lagoon Regional Park, a 45-minute drive from the City of Victoria, and the beach where Syd and Kendall end up on their hike was modeled after French Beach Provincial Park, which is halfway between Sooke and Jordan River, an hour-and-a-half drive from Victoria.

In the end, Port Raven is a small coastal city that could exist in Canada just as well as it could in the United States…or on the other side of the world or on the planet Tatooine. That’s the wonder of writing fiction. It can be anything you make it.

What do you think? Do you enjoy trying to figure out if the author has based a fictional setting on a real place? If you’ve read TimeBlink, did you think Port Raven and Chapman Falls were legitimate places? If you hail from the US, did you notice any glaring “Canadianisms” that might have been missed in the final editing process? I welcome all feedback, particularly since I’m in the middle of writing book two: TimeBlink: Flight 444.

*The City of Victoria proper has a population of about 90,000 and is located within Greater Victoria, which encompasses thirteen municipalities and has a population of around 368,000.

Header image of the Olympic Mountains and Downtown Victoria from Mount Doug, Victoria, BC, Canada Adobe/Wirestock